Joyce Ashuntantang, Ph.D.

In February 2011, I participated in a poetry festival in Granada, Nicaragua. One of our poetry sessions was at the main police barracks. I was not only pleasantly surprised to see police officers enjoying our poetry presentations, I was elated when they shared their own poetry. Of course my surprise stemmed from the fact that some police officers around the world have abused their role as keepers of the peace, so it was strange to see police officers castigating some of the practices we have come to associate with their kind. Perhaps, this positive experience in the police barracks in Nicaragua prepared me to welcome Green Hills from the Soldier-playwright, Ayang Fred.

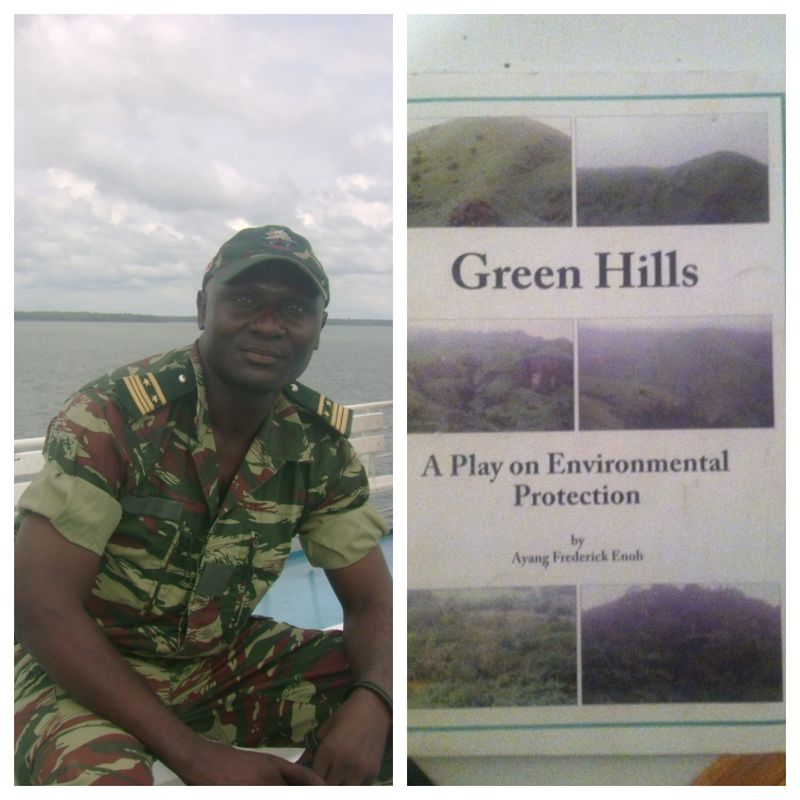

Major Ayang Frederick Enoh, Author of Green Hills: A Play on Environmental Protection published by Awah Publishers, Cameroon. ISBN 9956-586-02-1

A soldier has the judicious task of protecting the land; a writer, I would argue, also has the arduous task of protecting the land by creating works that advance the visions and ideals of his or her respective community. The playwright of Green Hills, Ayang Fred, is no ordinary soldier; he has earned the rank of Major (Commandant) and heads the Military Security unit in Buea, better known by its French Acronym, SEMIL. He is equally no ordinary writer. He brings to this creative exercise his expertise as a consummate stage and TV actor. Before he joined the army, he performed such diverse roles as Othello in Shakespeare’s Othello, Thomas Beckett in T. S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral, Lagham in Bole Butake’s Lake God, Adamu in Through A Film Darkly, and Remy Babila in Kwasen Gwangwaa’s Our Cousin. I can attest to his engaging performing skills since I acted alongside him in almost all of the above mentiond plays beginning with Othello where I was Desdemona. It is therefore not surprising that the collocation of Fred Ayang’s roles as soldier and writer has culminated into the creation of a play with a didactic value.

Green Hills is a play that dramatizes the importance of the community to protect its environment not only as an immediate source of livelihood but for posterity. Yet Ayang’s didactic stance in Green Hills is not a lone venture. Literature in Africa has always served a utilitarian purpose. Our ancestors told folktales, riddles and songs to educate and promote positive value systems in the community. Art for Art sake did not simply exist. It is therefore not surprising that modern African Literature from its inception has been didactic. Chinua Achebe crystallized this in his essay “The Novelist as Teacher” where he argued that “The writer cannot expect to be excused from the task of re-education or regeneration that must be done. In fact he should match right in front.” (45). Achebe made this call in 1965 when most African countries where still coming out of the grip of colonialism. For Achebe then his role as a writer was quite clear. As he put it, “ I would be quite satisfied if my novels (especially the ones I set in the past) did no more than teach my readers that their past with all its imperfection was not one long night of savagery from which the first Europeans acting on God’s behalf delivered them”. (45). Osundare re-iterates Achebe’s stance by stating “…the writer by virtue of his ability to transcend quotidian reality, has a duty to elate not only how things are, but how they could or should be. He must not only lead the people to the top of the mountain and point out the Promised Land; he must also show them how to get there” (12). In Cameroon, writers like Bole Butake, Bate Besong, Victor Epie Ngome, and Nkemgong Nkengasong, Babila Mutia, Makuchi, Anne Tanyi-Tang and Mathew Takwi share Achebe and Osundare’s vision. These writers have used their works as platforms to educate the people on various societal issues. According to Shadrach Ambanasom, writers like these, “…side with the people, the down trodden and the left-out, subtly giving them a sense of direction”. Therefore, Ayang Fred as a playwright has joined a long line of African artists, from the anonymous producers of oral literature through modern African literature artists who have successfully used literature as a didactic tool.

However, what makes Fred Ayang’s Green Hills, a celebratory event is that there is a growing concern that African writers may be veering off this path. In his keynote address to the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) on November 30 2011, the poet, Tanure Ojaide expressed his angst about African writers who do not only abdicate the role to educate but who even find ways of questioning the whole raison d’etre of “African literature”. Ojaide then goes ahead to state categorically that “African writers must work harder to deploy their writings to be at the vanguard of raising the life expectancy, education, and standard of living of African peoples”. Ayang Fred seems to have fulfilled this requirement in Green Hills.

One of the major crises of our times is the awareness that we need to protect our environment or else it will not be able to sustain us in the foreseeable future. Since the 1997 Kyoto protocol on global change there have been several international gatherings from Nairobi through Canada to Copenhagen to Durban, with the aim of finding lasting solutions to problems of climate change. It is a matter of life and death in Cameroon and other African countries where most of the population is still dependent on subsistence farming. One of the ways to combat this crisis has been to educate the local population of their responsibility towards the environment. This job for the most part has been taken up by Non Governmental Associations (NGO) and Theatre for Development (TFD) practitioners who develop skits intended to bring the pertinent issues dramatically home. However most of this TFD scripts are sociological in nature with very little literary merit. That is why Tanure Ojaide amplifies his call for relevant literature with this caveat:

In some cases, the writers emphasize contentious issues that grab the attention of foreign agencies that fund local NGOs. One can therefore write on HIV/AIDS, female circumcision, child-bride, “breast ironing,” environmental degradation, human rights, and other subjects as if doing a sociological rather than a literary work. The point being made is that there must be a balance of content and form for a work to be good literature.

It is therefore very refreshing to note that while Ayang Fred’s creative consciousness tackles the way local communities can protect their environment, his skillful handling of characterization, dialogue and plot make Green Hills a highly entertaining and successful piece of art.

When the Fon summons the village elders to enjoin them to enforce the planting of trees and to stop the random burning of bushes, it is not surprising that he meets resistance. His request alters the way of life the village has been used to for ages. There’s chaos as some of the women are disturbed from planting trees but eventually those who resist are educated and the village is unanimous on the merits of tree planting to sustain their environment. If this were all, then Green Hills will not be different from some of the hastily crafted sociological tracts passing for plays which people use to solicit financial remuneration from NGO’s.

On the contrary, in Green Hills, Ayang taps from his vast experience as an actor to incorporate salient elements of drama in his play which elevate it to enjoyable art. He intricately weaves a play that despite its relative short length incorporates a main plot and a sub-plot which is also relevant and didactic. The story of men like Atah and Maricus who beat their wives is skillfully tied into the main plot which hinges on seeking solutions for environmental degradation. Maricus, the chief culprit of wife beating is not only ridiculed but it is clear that the community does not condone his actions. Although it would have been great to see him shed his ignorance in the domain of wife beating, one can expect that his change at the end of the play will permeate other parts of his life. Another engaging aspect of Ayang’s craft is his exploitation of humor. The conscious and unconscious abuse of the environment is a crisis which threatens the life of whole communities like the community in Green Hills, but Ayang Fred sprinkles humor to not only lighten the atmosphere but to also give dimension to certain characters as exemplified in the following dialogue:

Atah: What can be the problem? Everything is fine in the

land as far as I can see. Did anyone steal a goat this last weak?

Acha: No! No! after the treatment meted out to the last goat thief

I don’t think someone can risk stealing again in this land

Atah: Ok, wait…a little. Just wait a little

Emme….emmeee wait a minute, have you beaten your wife again of late?

Acha: No, I have not beaten Abuuh now for a very long time. In fact, it is

about…three…four days, yes it is four days since I last beat her.

Acha’s responses are funny because of the seriousness with which he says ridiculous things. For example, it must be obvious to any reader or an audience that “Four days” is not a “very long” time. Therefore in saying that it has been four days since he beat his wife he indirectly indicts himself and is no better than Maricus whom he believes is the worse offender. This gap between the truth and the manner in which it is delivered becomes a site for humor. Acha’s humorous utterances also frame his character. His utterances are not only funny, they sound naïve. He seems to be immature, and does not come across as one who deserves to lead a household. Therefore, one is not surprised when later in this same conversation the playwright tells us in stage directions that he “laughs boyishly”.

As a consummate actor, one can tell that Ayang Fred visualizes his characters on stage as he creates them. A versatile actor who has played the role of an army general (Othello, in Shakespeare’s Othello) and the role of a houseboy (Adamu in J.C. De Grafts Through a Film Darkly) with equal dexterity, Fred Ayang has created characters that are identifiable and memorable. The Fon is not only dignified but he is humble enough to seek a second opinion, yet he knows when to be firm to bring about results. On the other hand, Maricus is a playful rogue who seems to epitomize all the ills in the land. Atah deftly dissects him in the speech below:

This man will kill us all one day:

Who took palmwine into church…Maricus

Who drove the Reverend Father away…Maricus

Whose wife is always on the run…Maricus

No wonder the Reverend Father changed your name

From Mbahwifi to Maricus saying it was too long.

Although Atah’s claims here cannot be disputed, they nevertheless do not complete the character of Maricus. Maricus is more than all this. He may be guilty of causing trouble in the community but his questions with regards to the planting of trees are genuine and show him as one who has the ability to think critically. In fact his questions become our questions. If Maricus alienates the reader or audience because of his actions outlined by Atah , the reader and audience would easily identify with Maricus’ questions to the Fon:

The Fon says “everybody go out and plant trees” yes

people go out because the Fon has said it.

But I put a simple question to the women.

Whose land will it become after the trees are planted on it?

By the way what will the trees do to me?

Will the Fon own all the trees I will plant on my land?

Anyway what kind of trees are we planting?

The Fon says “no bush fires”; does this mean that we will not hunt?

At the end when Maricus gets the answers to his questions, it becomes clear that he is not just a notorious nuisance in his community after all. Indeed the answers to these questions are meant for the audience as well who are extensions of the community on stage. One only hopes that Maricus will also eventually question the role of logging companies who are also guilty of cutting down trees with impunity.

So where is Ayang Fred’s sense of responsibility to his community coming from? Is it from the soldier in the writer, or the writer in the soldier? The answer does not seem to matter. The hope is that Ayang’s dual responsibility as a soldier and writer will fuel more creative works that will enhance the quality of life in Cameroon and beyond.

Works Cited

Achebe, Chinua “The Novelist as Teacher”, Morning Yet On Creation Day. London:

Heinemann, 1975. 42-45

Ambanasom, Shadrach. Education of the Deprived. Yaounde: University of Yaoundé

Publishing House, 2003.

Ojaide, Tanure. “Homecoming: African Literature and Human Development”,

unpublished keynote address to the Association of Nigerian Authors,

November 30th 2011, Abuja, Nigeria.

Osundare, Niyi. The Writer as Righter: The African Literature Artists and His Social

Obligations. Ibadan: Hope Publications, 2007